Bryan William Jones, Robert E. Marc and Rebecca L. Pfeiffer

1. Introduction

Retinal degeneration and remodeling encompasses a group of pathologies at the molecular, cellular and tissue levels that are initiated by inherited retinal diseases like retinitis pigmentosa (RP), genetic and environmental diseases like age-related macular degeneration (AMD) and other insults to the eye/retina including trauma and retinal detachment. These retinal changes and apparent plasticity result in neuronal rewiring and reprogramming events that include alterations in gene expression, de novo neuritogenesis as well as formation of novel synapses, creating corruptive circuitry in bipolar cells through alterations in the dendritic tree and supernumerary axonal growth. In addition, neuronal migration occurs throughout the vertical axis of the retina along Müller cell columns showing altered metabolic signals, and retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) invades the retina forming the pigmented bone spicules that have been classic clinical observations of RP diseases.

Retinal photoreceptors drive signal processing networks in the neural retina comprising bipolar, horizontal, amacrine and ganglion cells. It has been historically thought that retinal degenerative diseases such as RP affect the sensory retina, leaving the neural retina relatively unscathed. This is incorrect as the resulting loss of rod and cone input to the neural retina constitutes deafferentation and remodeling at the cellular and molecular level becomes unavoidable (1-23).

Retinal degenerative diseases have a number of potential initiating events that result from naturally occurring disease processes (24), trauma like retinal detachment (25, 26) or any of the forms of retinitis pigmentosa (5, 24, 27, 28) but regardless of cause, if photoreceptors are lost, particularly cones, a sequence of progressive events is initiated that induces negative plastic remodeling of the neural retina (9-11, 14-16, 20, 23, 29). Essentially every disease process that results in photoreceptor loss triggers retinal remodeling as the final common pathway culminating with cell death and topological restructuring of the retina. The progression of retinal remodeling is similar to the negative plasticity that occurs in CNS pathologies like trauma and epilepsy and constitutes substantial impediments to rescue strategies of all types.

2. Phases of retinal remodeling

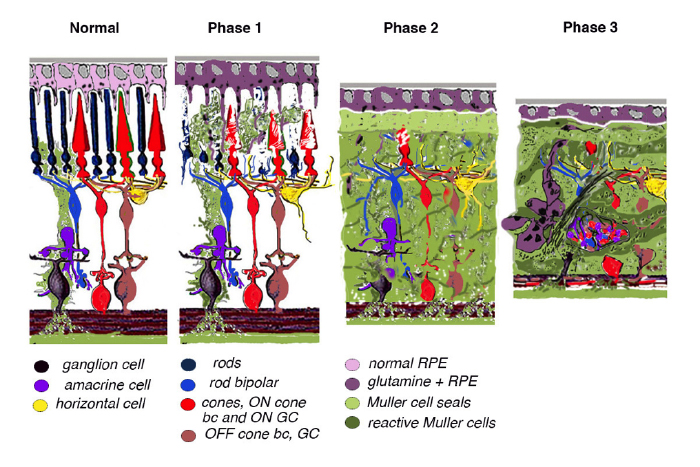

Retinal remodeling occurs in phases: In phase 1, photoreceptor stress initiates early remodeling & reprogramming events. In phase 2, microglia, Müller glia and RPE cells become involved. Outer nuclear layer (ONL) thinning/ablation occurs and cell stress pathways are engaged while Müller cells begin sealing the retina off from the choroid. In phase 3, de novo neurite formation, rewiring and neuronal death start a process that continues to progress with neuronal translocation and massive topological restructuring of the retina. We will show in this chapter that all retinal degenerative diseases examined to date including natural, crafted and induced models demonstrate remodeling to some extent and the severity of the negative plasticity depends upon coherency of insult and whether or not cones survive. Additionally, the early retinal remodeling is often clinically occult and occurs prior to any notable clinical fundoscopic imaging.

3. Age-related macular degeneration (AMD)

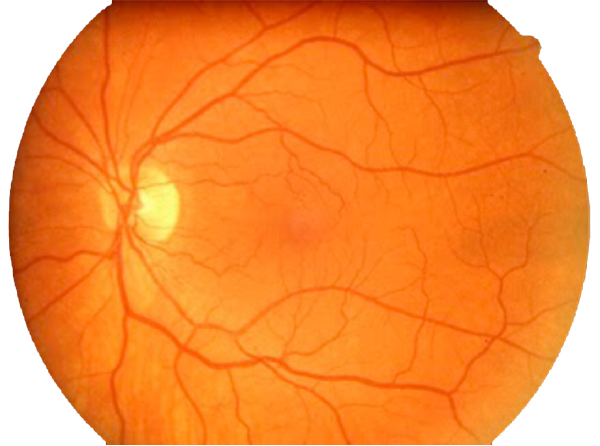

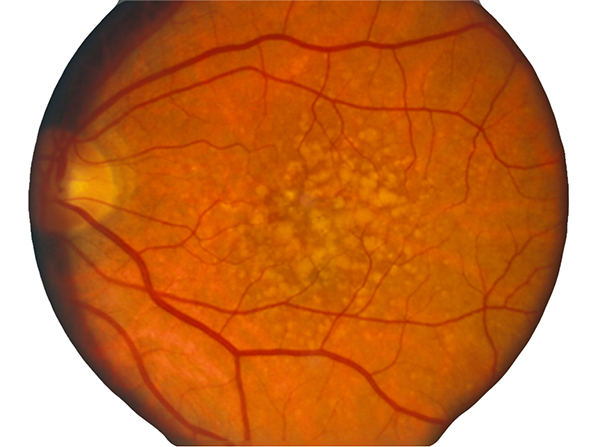

In contrast to normal retina (Fig. 1), AMD presents with another set of clinical findings including fundoscopic drusen or yellow spots as well as areas of chorioretinal atrophy seen in dry AMD also called geographic atrophy (GA) (Fig. 2). An animation of the progression of GA over 6 years can be seen here.

Histological presentations of AMD show drusen development in dry AMD that appears to induce photoreceptor cell stress and loss (30). Wet AMD is another disease process entirely that results in death of photoreceptors due to blood vessel development and leakage of blood and serum into the neural retina. This sub retinal blood can also result in RPE detachment that can have its own retinal degenerative mechanisms as well as direct retinal death.

Clinically, patients with dry AMD will often complain of difficulty seeing at night or in dark environments, and of needing brighter lights to work with. They report problems with decreases in color saturation and increases in blurriness of printed words or images in the central part of their vision. Vision deficits progress until there are distortions in the central visual field and ultimately blindness as the degenerative process progresses.

While most of the discussion in this chapter will focus on Retinitis Pigmentosa (RP), it should be noted that the terminal phases of retinal remodeling discussed above and the plasticity and remodeling that will be elaborated on below also occur in AMD, particularly dry forms of AMD (30).

Figure 2. Fundoscopic image of classic drusen seen in AMD in human eye. AMD presents with another set of clinical findings including funduscopic drusen or yellow spots as well as areas of chorioretinal atrophy seen in dry AMD also called geographic atrophy (GA). An animation of the progression of GA over 6 years can be seen here.

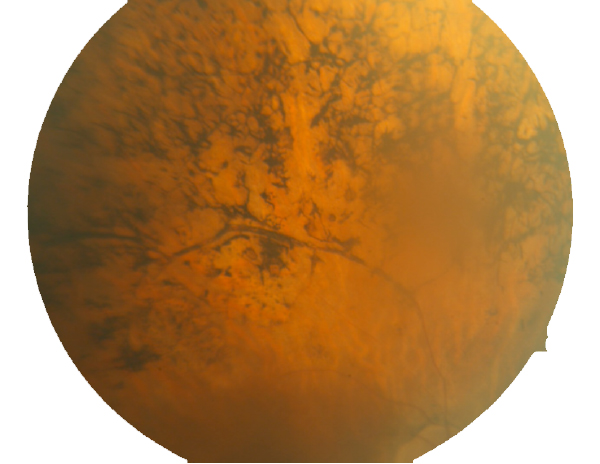

Figure 3. Fundoscopic image of advanced RP seen in a human eye.

4. Retinitis pigmentosa (RP)

RP is a progressive, neuro-degenerative disease that typically begins in the periphery and progresses to the center of the retina. There are a number of different forms of RP with a variety of initiating etiologies including defects in the retinal pigment epithelium, defects in rhodopsin processing and trafficking, defects in rhodopsin stacking, defects in the cilia and many others. Generally speaking, however, RP comes in 3 main categories that include rod-degenerative, mixed rod/cone degenerative and debris-associated forms like mertk defects and models like the light damage models in albino mice/rats. Regardless of the initial insult, the final outcome is the same: photoreceptors undergo stress and subsequent cell death, which effectively deafferents the neural retina, resulting in neural remodeling events that alter the topologies and circuitry of the neural retina.

The clinical sequelae depend upon the broad category of RP involved. Initially, the rod/cone dystrophies manifest with complaints about night blindness beginning in the teenage years or early 20’s. Changes in the electroretinogram (ERG) can often be observed prior to fundoscopic findings, most notably in the X-linked form of RP as rods begin to undergo stress and cell death. This reveals a fundamental finding: Photoreceptor function is altered or impaired prior to photoreceptor cell death and gross alterations in the histology become evident. Glutamate channel permeation studies with 1-amino-4-guanidobutane or agmatine (AGB) in early degenerate retina also support this finding by documenting alterations in subpopulations of bipolar cells and glutamate channel expression before loss of bipolar cell populations (23, 31).

By the time this classic fundoscopic image (Fig. 3) appears, retinal degeneration is advanced, many cell populations have been dramatically altered or lost and Müller cells have become hypertrophic, acting as highways for neuronal translocation as well as pigment translocations into the inner retina from the RPE (23, 31).

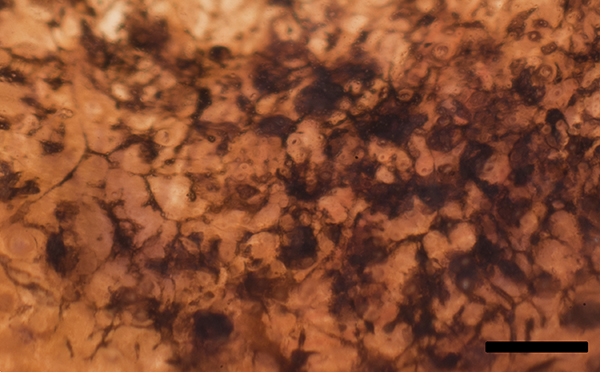

Pigmented bone spicules in retinitis pigmentosa are accumulations of pigment granules from the RPE that have been coalesced into ribbons and clumps and pulled down into the neural retina. Figure 4 is a backlit and magnified image of a globe and intact retina that is focus stacked to illustrate the structure of pigmented bone spicules in an intact globe.

When you consider how the pigmented bone spicules form, the status of other classes of cells in the retina becomes a question. This is particularly true in advanced cases of RP that are being proposed for bionic and biological interventions that we’ll discuss at the end of this chapter. Visual science has been examining the histology of retinal degenerative diseases for some time and there have been lots of descriptions made, yet somehow important features have gone missing or were briefly discussed, then forgotten. Jaissle et. al. in 2010 (32) looked at how pigmented bone spicules form in the rhodopsin knockout mouse model rho-/- and concluded that RPE pigment granules migrate along blood vessels. However, we now know that Müller cells act as conduits of migration that are seen not only in the rho-/-, but in many other models as well.

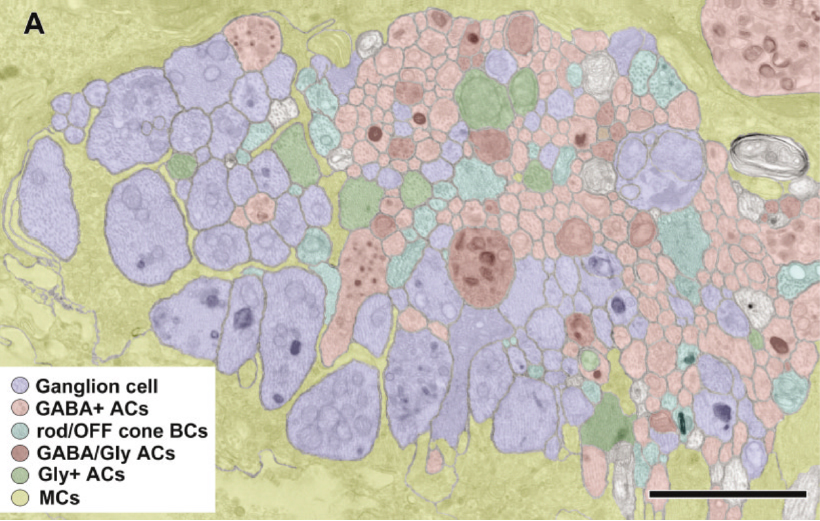

Considering Figure 4 and the obvious changes to retinal topology that are demonstrated in late stage RP, the condition of all of the individual cell classes in the retina as well as their connectivities comes into question. If you do an accounting of the types of cells that make up a retina, you find upwards of ~82-84 classes of cells that will each be affected in different ways in degenerate retina. Nominally, we have 1 transport epithelium class, the RPE, 3 photoreceptor cell classes composed of 2 cone photoreceptor classes and 1 rod photoreceptor class, 2 glial cell classes: Müller cells and Astrocytes. 2 horizontal cell classes (1 horizontal cell class in the mouse eye in Figure 5), 2 vascular cell classes, 35 amacrine or association cell classes, 10 bipolar cell classes, 1 immune cell class and 18-20 ganglion cell classes (33).

5. Historical histological methods

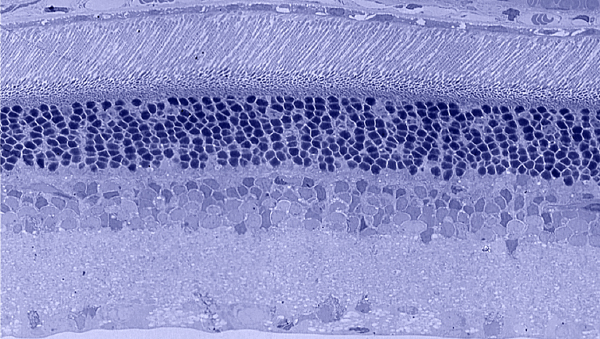

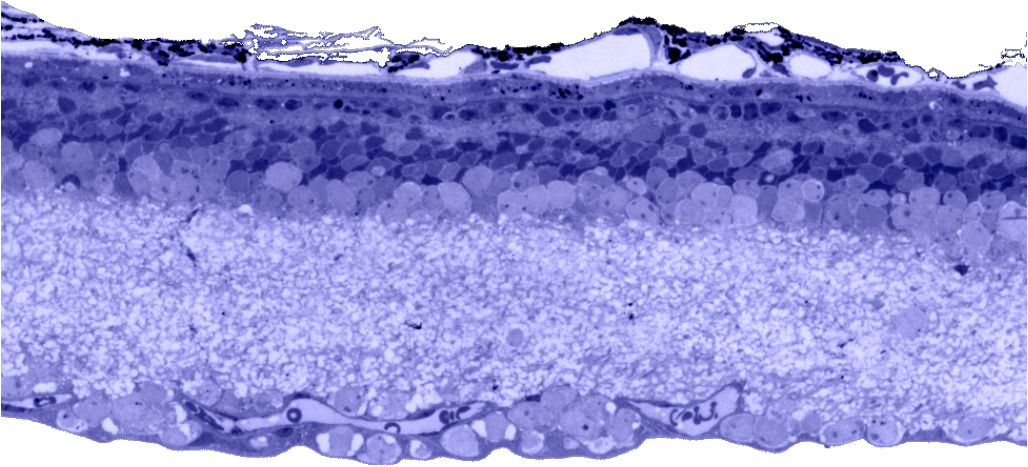

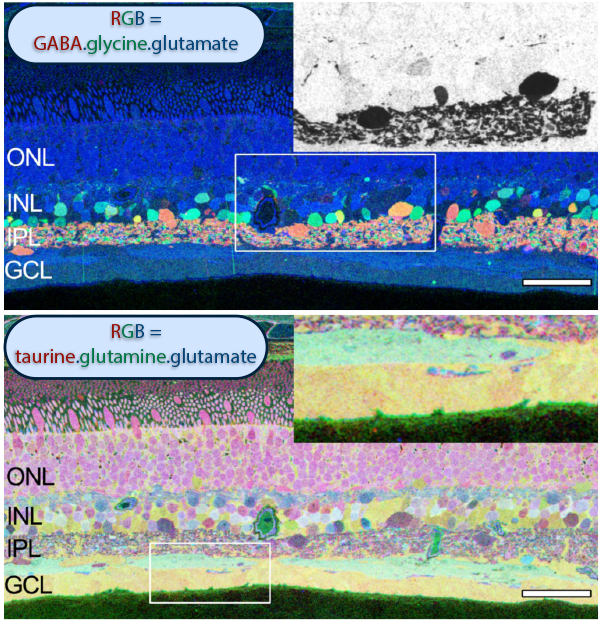

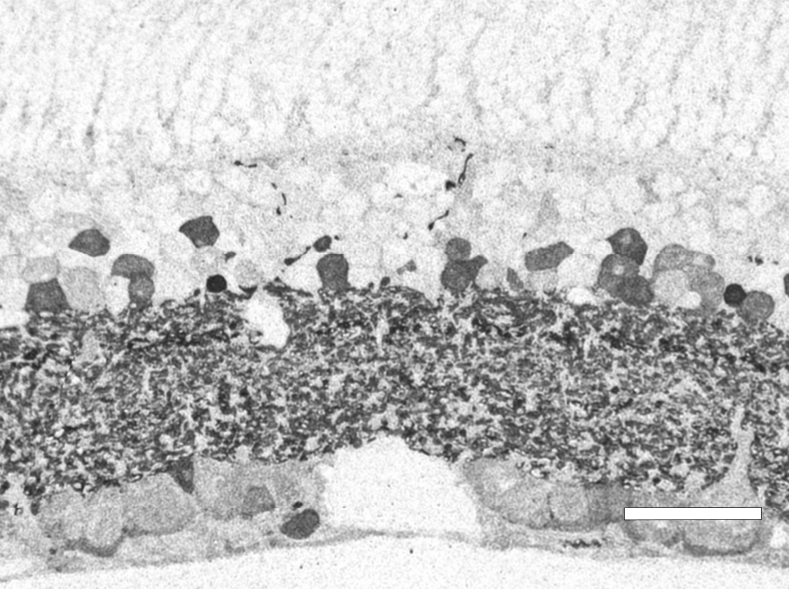

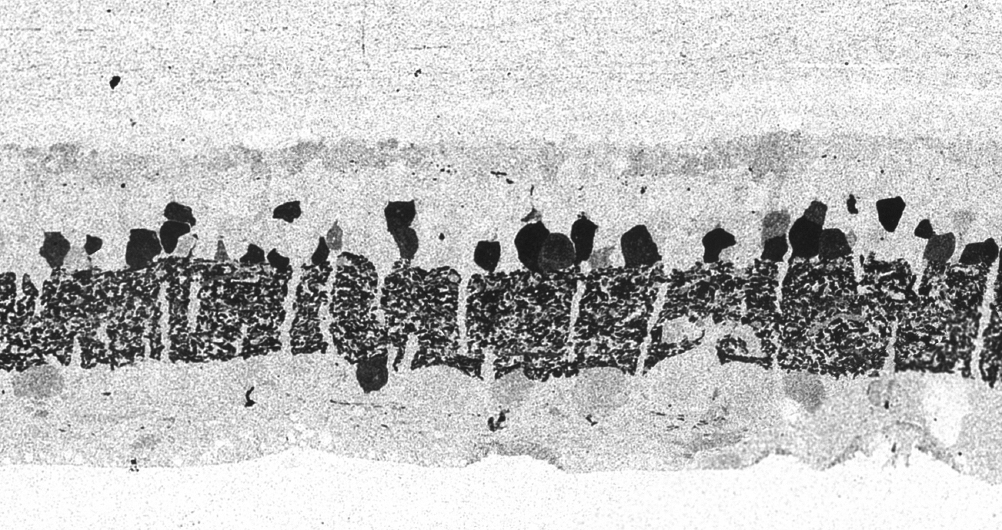

Traditional histological preparations like toluidine blue in figure 5 and figure 6 are the common currency in much of the literature and they give us the ability to easily discriminate layers and count the numbers or layers of photoreceptor cell bodies which has been a traditional measure of the level of integrity of the retina. These measures give us morphometric descriptors and provide some metric for degree of degeneration.

It turns out that this type of histology while incredibly informative, got us, the vision community into a bit of trouble over the past few years. Examining figure 6 seems to demonstrate a thinner outer nuclear layer that has been described as partial thickness, but the rest of the retina, at least here, looks OK, leading many to make assumptions on the level of intactness of the neural retina. When discussions of retinal rescue arose, along with subsequent strategies designed to intervene and cure blindness, they were based upon this assumed level of knowledge about retinal integrity, to rescue vision.

6. Plasticity in the retina

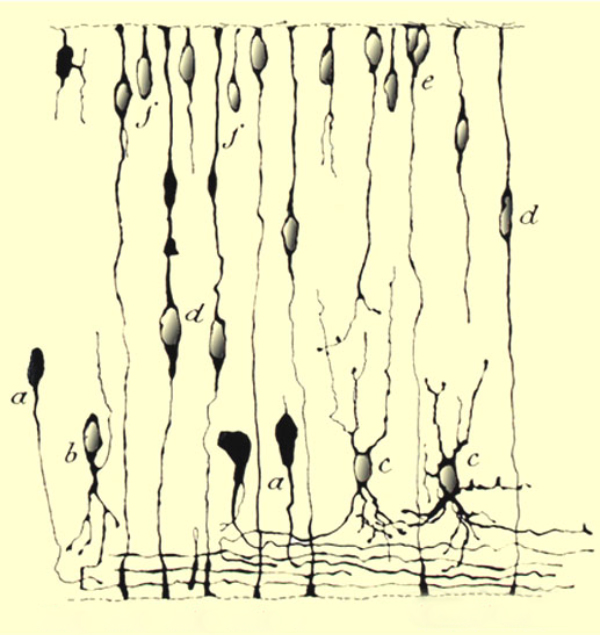

Of course, the retina is neural tissue and plasticity in the central nervous system (CNS) or retina is not a new concept. We have also known for quite some time that the developing retina is highly plastic. This knowledge goes back to 1933 with Ramon Y Cajal in his elegant illustrations of Golgi stains from developing retina shown in figure 7. (34).

Figure 7. Ramón y Cajal’s illustration of developing retina from 1933 (34).

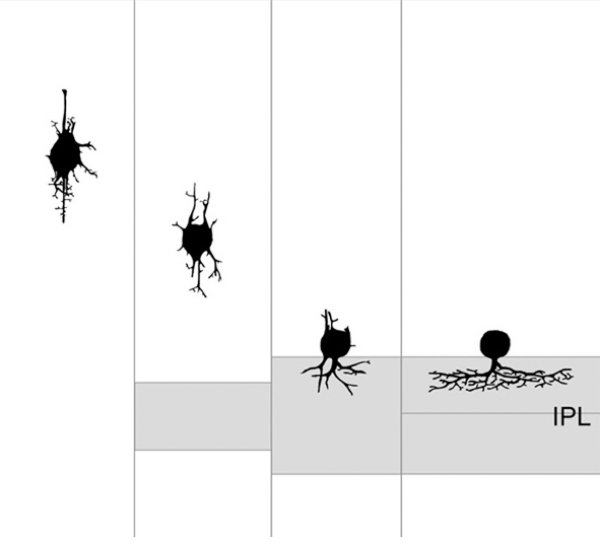

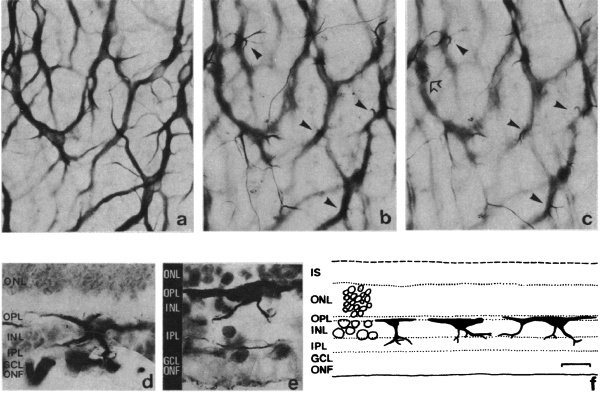

Another classic example of retinal plasticity in development was illustrated by Hinds and Hinds in 1978 (35) (Figure. 8) with an elegant serial section study that showed amacrine cell neurite development from embryonic day 13 to 17. Hinds and Hinds also explored autoradiographic studies on the origin of cells prior to E15. Interestingly, Hinds and Hinds also confirmed the Cajal observations of bipolar shaped amacrine cells in the developing outer ventricular layer 45 years prior.

Figure 8. Proposed sequence of amacrine cell neurite development from serial EM studies from Hinds and Hinds, 1978. (35).

Over the last 40 years many studies of retinal development have shown how the different retinal cell types develop and go through various morphologies and migrations through the retina to finally reach their mature retinal positions and involvements in neural circuits. The interactions of cells with others and establishment of synaptic circuitry often with pharmacological as well as light and pattern stimulation leads to a mature retina. See chapters in Webvision by Ning Tian, Rachel Wong and Marla Feller concerning these developmental stages in retinal organization. All of these studies have shown conclusively that the developing retina is very plastic. However, it was assumed that the adult retina remained more or less hard-wired once established.

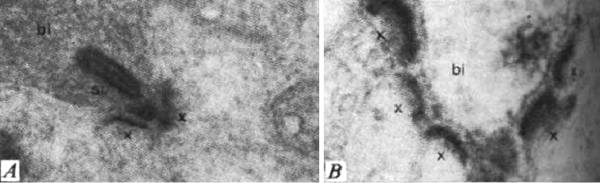

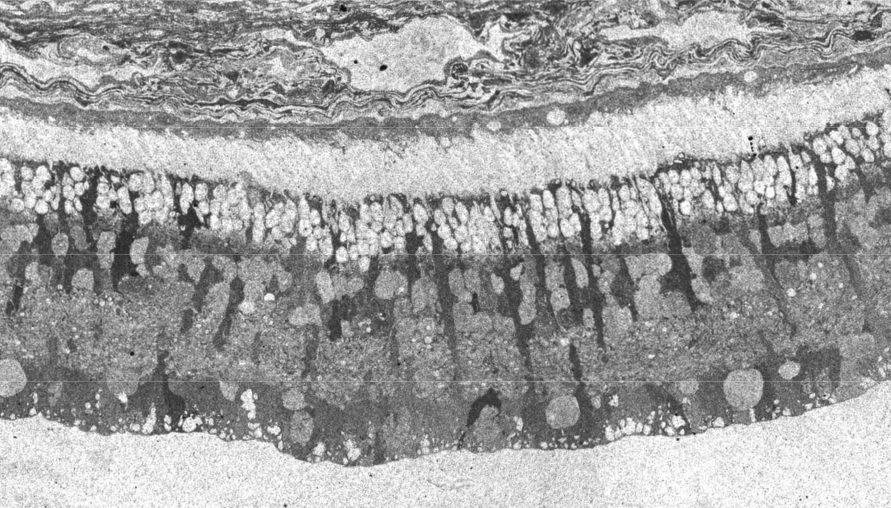

Some clues that this is not so came from studies in non-mammalian species. Fish are known to add rod photoreceptors and some secondary retinal interneurons in the retina throughout life (36-38). Moreover, amphibians can regenerate a complete retina and even connections between retina and brain when the eye is damaged (39). A more subtle instance of plasticity in the submammalian retina was shown, again in the fish, as a response to just the daily light and dark cycle. There are retinomotor movements of the retinal pigment epithelium in light and dark in fish retina for instance (40). Additionally, there is evidence of neural plasticity in the photoreceptor synapses with horizontal cells with coming and going of spinules according to light conditions (see chapter on horizontal cells in webvision) in the adult fish retina. Furthermore, the bipolar synapses in the inner plexiform layer show synaptic apparatus i.e. synaptic ribbons, appearing and disappearing with light and dark adaptation (Figure 9) (41).

But fish possess a more sophisticated retina than the mammalian because so much visual information processing goes on the retina as compared the mammal where the equivalent visual processing takes place in the brain (Dowling’s original concept of simple mammalian retinas versus non mammalian complex retinas, (42). So the question of plasticity in the adult normal mammalian retina had not been established until recently.

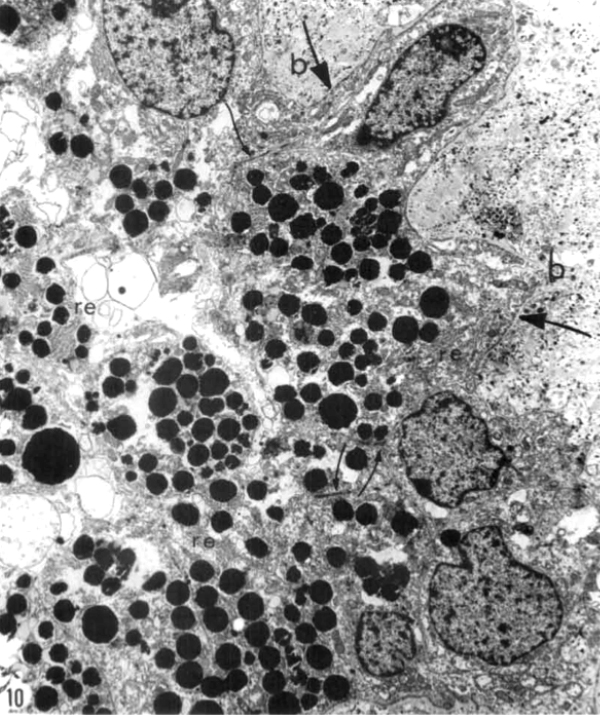

However in 1984, Peichl and Bolz (43) exposed retinas to kainic acid to induce structural remodeling (Figure 10) which they described as dose-dependent morphological changes in horizontal cells of adult mammalian retinas (cats and rabbits). Of course they found that high concentrations of kainic acid killed the cells, but when exposed to sublethal doses, horizontal cells contracted their dendritic fields and sent sprouting processes into the inner retina. Their conclusions were, quote: “It appears that kainic acid can induce neuronal growth as well as degeneration and that the potential for morphological plasticity is still present in neurons of the adult mammalian retina”. So under certain experimental conditions it appeared that some retinal neurons could remodel and plasticity was suggested for the first time in species other than fish.

We now know from studies of retinal degenerations that adult mammalian retinas can undergo substantial plastic and aberrant reorganization in response to damage. The rest of this chapter illustrates plasticity in the retina under traumatic and degenerative retinal disease.

7. The plasticity and remodeling that occurs in retinitis pigmentosa like diseases in mammalian retinas

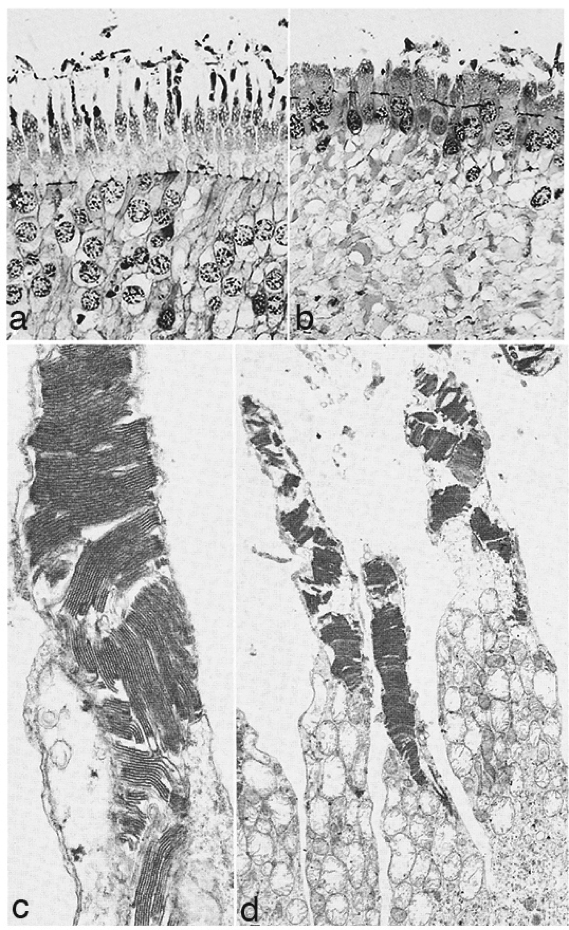

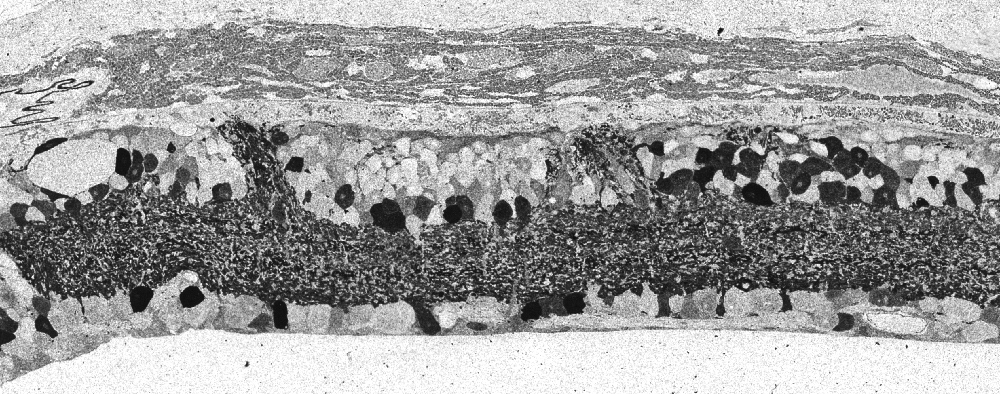

It has been already mentioned that classical histological examination of human retinas with retinitis pigmentosa (RP) or rodent models with this type of degeneration were being done in the 1960-70s, and gave the impression that apart from photoreceptors degenerating (Figure 6) the remaining neural retina was normal. It took electron microscopy to show that there were changes other that photoreceptor degeneration also occurring in the neuropil of the inner retina.

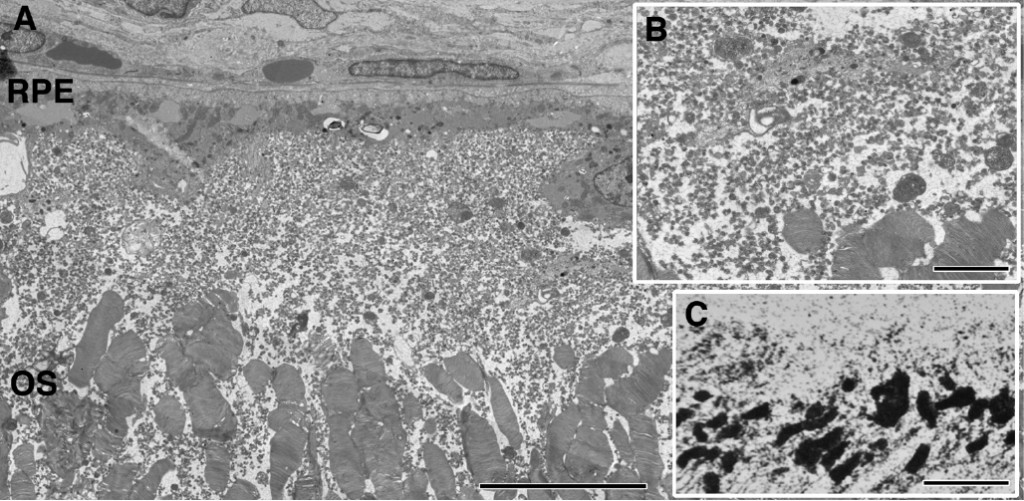

In 1967 and later in 1974, there were ultrastructural studies in the literature on RP that documented an autosomal dominant form of the disease (44, 45). Papers by Szamier, Berson et al (46, 47) followed later. These papers all concentrated on the pigment epithelium and state of the rods and cones in the diseased retinas simply because that is all that seemed to be recognizable as retinal elements by electron microscopy at the time. The rod photoreceptors in all these examples were degenerating or totally absent. The cones of the fovea were best preserved (Figure 11a) but outside the fovea cones were reduced to inner segment stubs (Figure 11b). Higher magnification of the foveal cones showed they had disorganized outer segment discs (Figure 11c and d), but presumably these were functional because the patient had corrected vision of 20/25 in the eye examined by EM ( Figure 11) (44). The foveal inner retina was not examined in this RP retina and inner retina in the parafoveal area was an indistinguishable tissue of vacuoles and debris (Figure 11b).

Kolb and Gouras (44) were also able to look at the bone spicules in this human RP retina (Figure 12). This electron micrograph shows that cells comprising the pigment clump are of the same type as the cells of the peripheral pigment epithelium. This observation pointed out that RPE cells had migrated into the neural retina, thus forming the characteristic bone spicules of advanced retinitis pigmentosa seen in fundus photography (Figure 4). This early finding could now be interpreted as plasticity and remodeling of retina in response to degenerating retinal integrity.

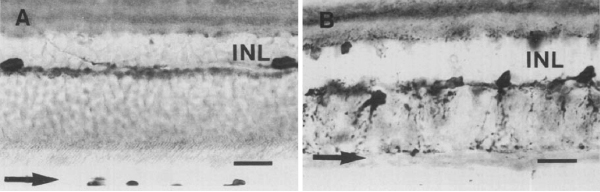

It was not until almost two decades later that another paper came out that examined aberrant plasticity in retinal tissues. The 1993 paper from Chu, Humphrey and Constable (48) showed that the RCS rat demonstrated retinal remodeling (though they called it disorganization) of horizontal cell processes in the degenerate retina (Figure 13). Interestingly, they also noted that the “disorganization” was not uniform across the retina with the most “disorganized” horizontal cells in the posterior pole where all outer nuclear layers had been lost. These horizontal cells also showed marked morphological aberrations with “swelling” or hypertrophy.

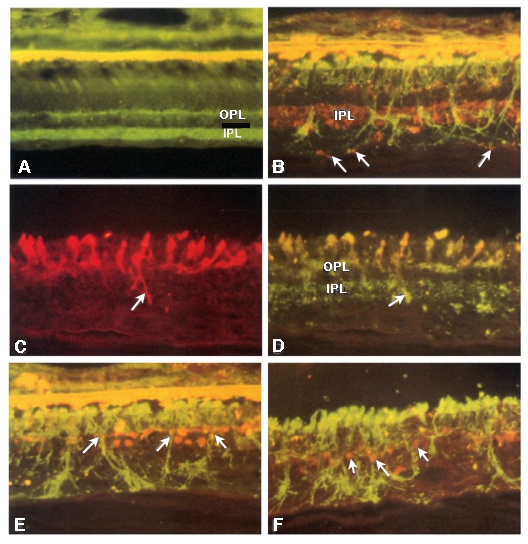

In 1995, Li, Kljavin and Milam (1) reported that rhodopsin positive neurites extended from the photoreceptor layer down into the inner retina and ganglion cell layer in 15 human RP samples (Figure 14). This was the very first paper that showed neurites sprouting from photoreceptor cells and demonstrated conclusively that rhodopsin delocalized into the membrane of the photoreceptor cell, apparently after mis-trafficking. The authors mention in the paper that “the rod neurites in the human RP retinas resemble the long, branched processes formed by rods cultured on Müller cells or purified N-CAM”. It turned out that they were more correct than they imagined as we will see later, Müller cells form the conduits or scaffolding for cellular migration in the degenerate retina. This paper was also seminal in that the authors were thinking about potential implications for therapies in this manuscript and suggested that these changes to the “retinal microenvironment may impede function integration of transplanted photoreceptors”, ringing the warning bell for the biological transplant community that largely went ignored for a number of years.

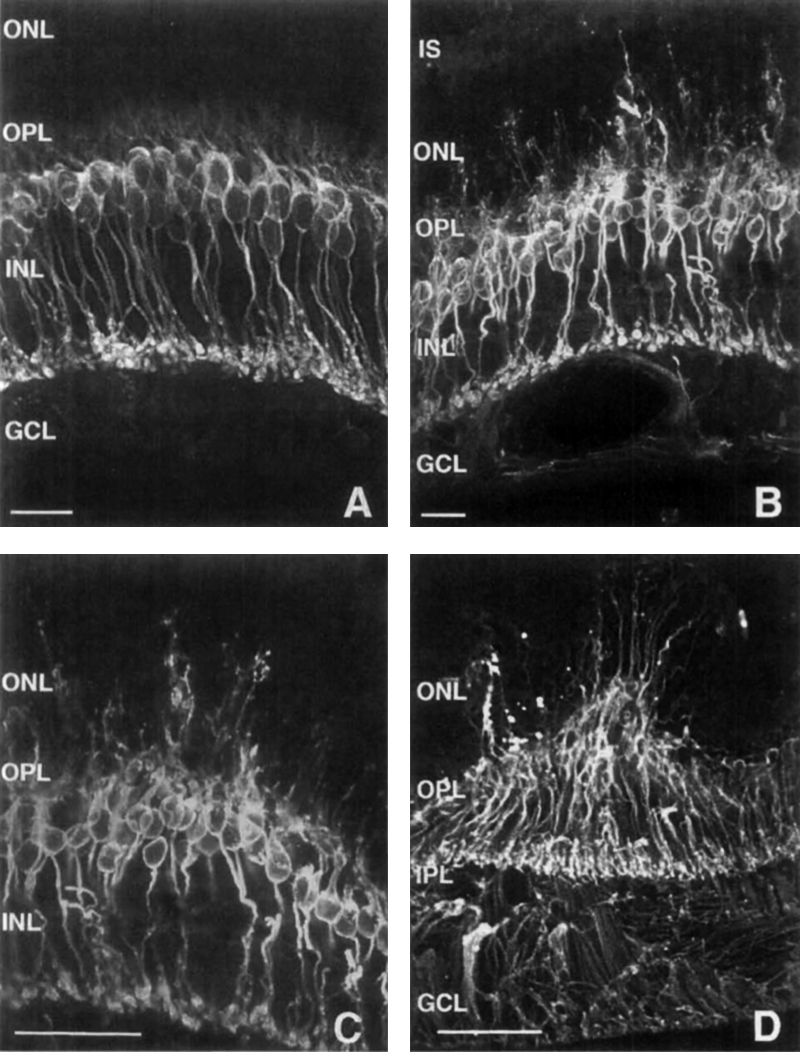

Three years later, in 1998, Lewis, Linberg and Fisher (26) explored horizontal and rod bipolar cells in experimental retinal detachment (Figure 15). They conclusively demonstrated aberrant sprouting of fine dendritic processes from rod bipolar cells projecting into the outer nuclear layer (ONL) in response to retinal detachment in the feline retina. They also noted horizontal cell processes growing into the ONL and concluded that processes from horizontal and rod bipolar cells “lengthen after retinal detachment, perhaps in response to a withdrawal of their presynaptic targets, the photoreceptor synaptic terminals. The important thing with respect to interventions for blinding diseases is that these authors also invoked the implications of sprouting inner retinal neurons for therapies like retinal photoreceptor transplant. This work is documented extensively in another chapter here on Webvision, Cellular Remodeling in Mammalian Retina Induced by Retinal Detachment.

Two years later in 2000, Fariss, Li and Milam (4) examined rod photoreceptors, amacrine cells and horizontal cells in human RP retinas and demonstrated aberrant sprouting in those cell classes, particularly in GABA positive amacrine cells and calbindin positive horizontal cells (Figure 16). They also noted that rod neurites that projected into the inner retina, and at least contacted the somas of GABA positive amacrine cells, though no mention of synaptic connectivity was noted. This study continued the previous work, and included GABAergic amacrine cells into those neurons in the retina that contribute to the rewiring phenomenon that was starting to emerge. Also of note in this paper, the authors note that these changes may form the basis for some of the psychophysical abnormalities noted by patients (phosphenes and visual hallucinations) as well as form the basis for progressive visual function decline in patients with RP and again reiterated from the Li et. al., 1995 paper (1) that these alterations may complicate vision rescue strategies.

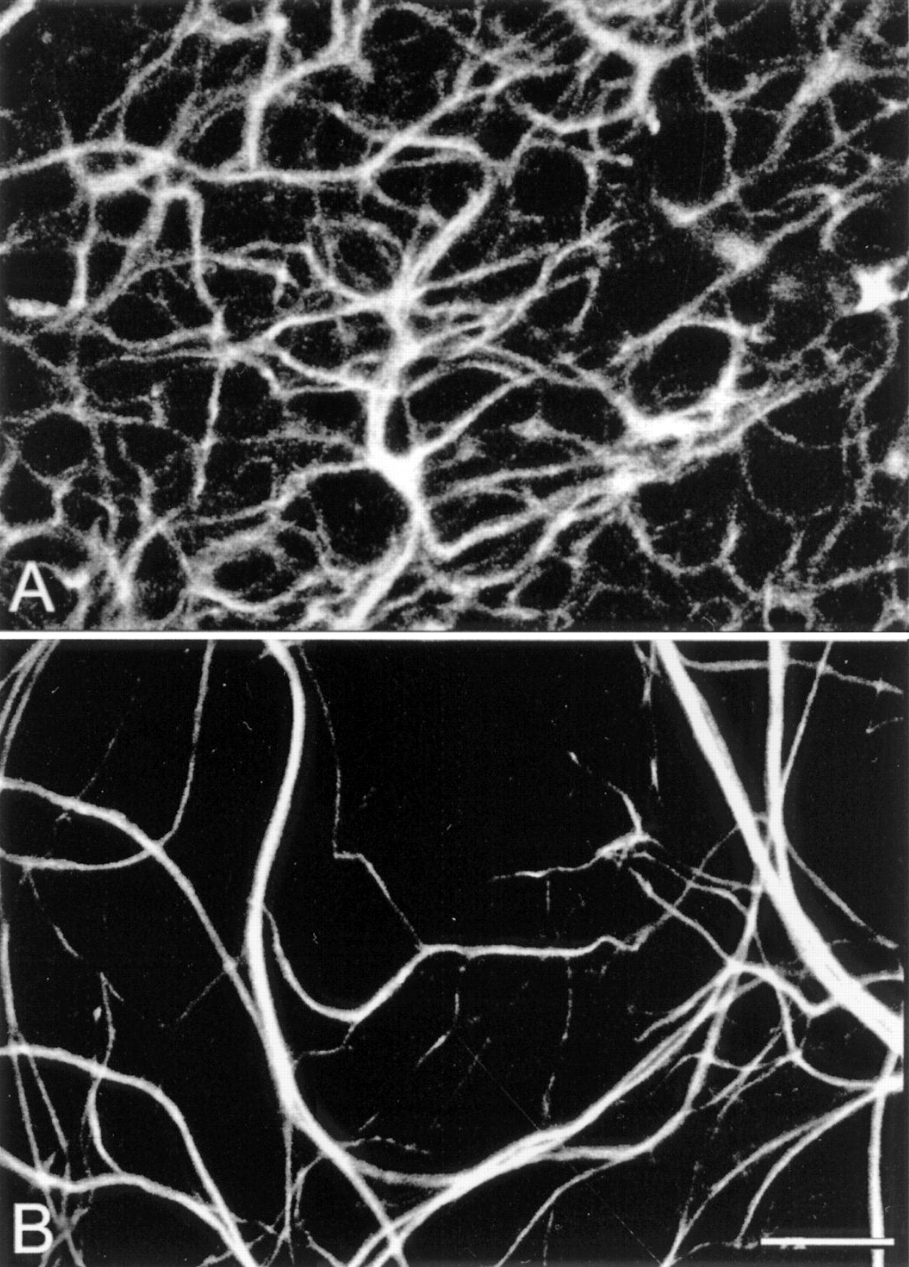

Figure 17. Whole-mount staining with neurofilament antibodies. Compare the tight network made by horizontal cell axonal endings in the OPL of wt retinas (A) to the loose arrangements of hypertrophic process in the rd (B). from Strettoi and Pignatelli, 2000 (7).

Also in 2000, Strettoi and Pignatelli (6) showed in the rd mouse, an animal model of RP, bipolar and horizontal cells undergoing “morphological modifications accompanying photoreceptor loss” (Figure 17). The authors concluded that these modifications were dependent upon photoreceptor loss and again raised the specter of potential impact on retinal rescue models.

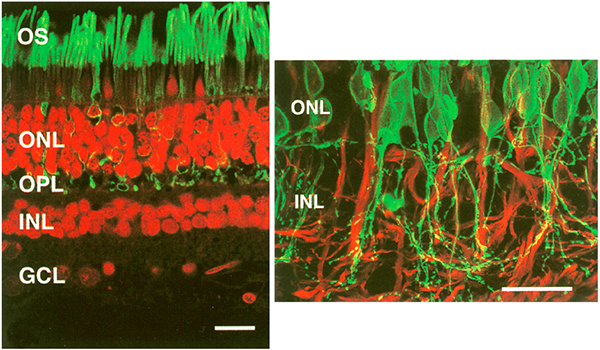

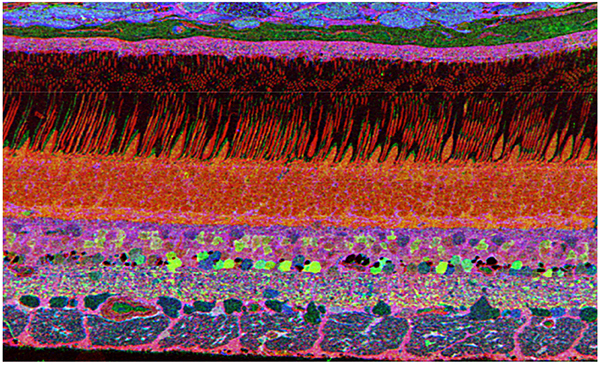

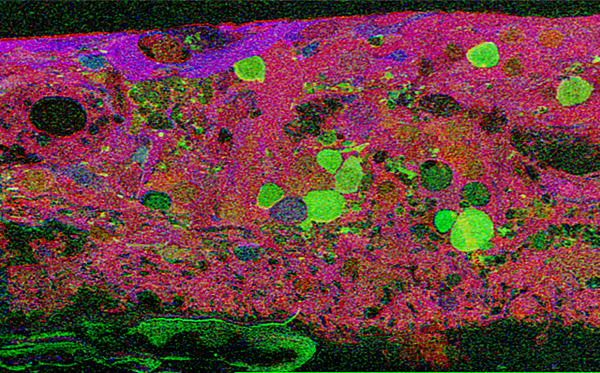

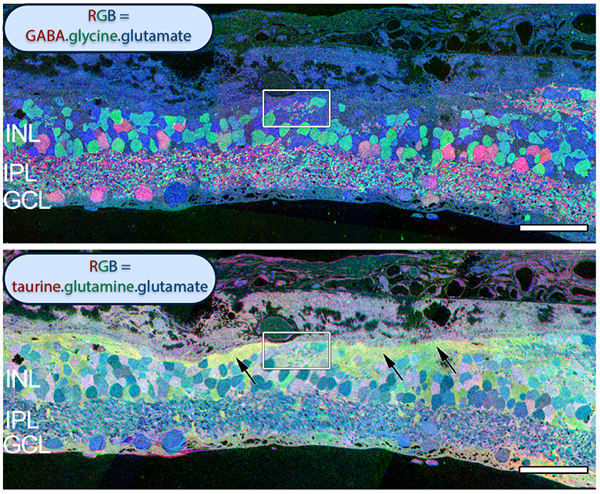

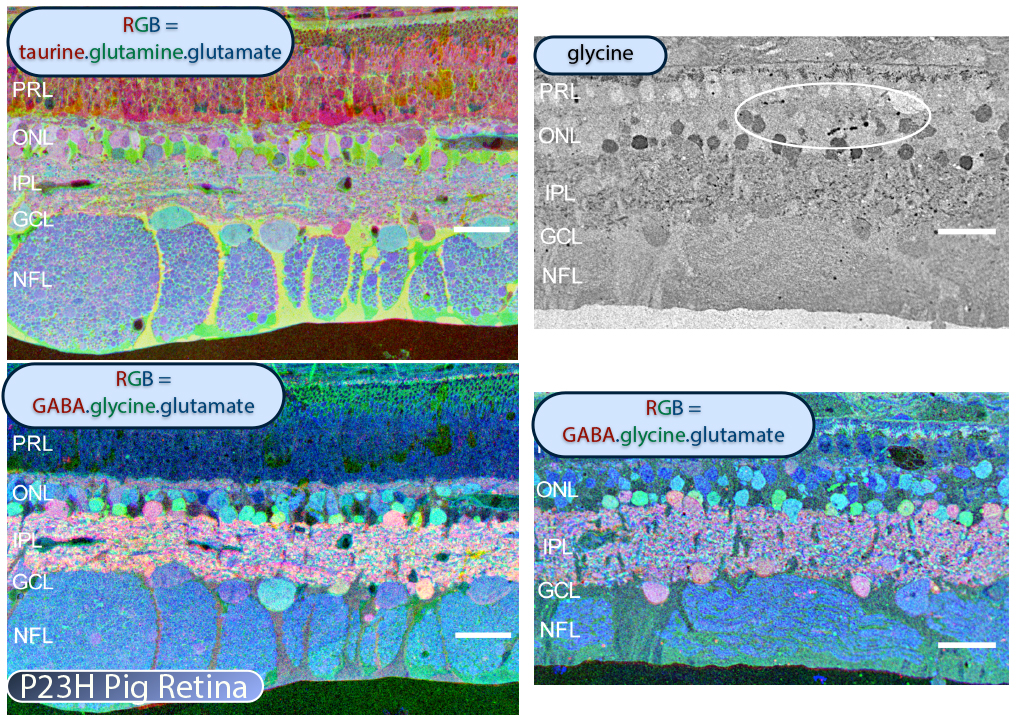

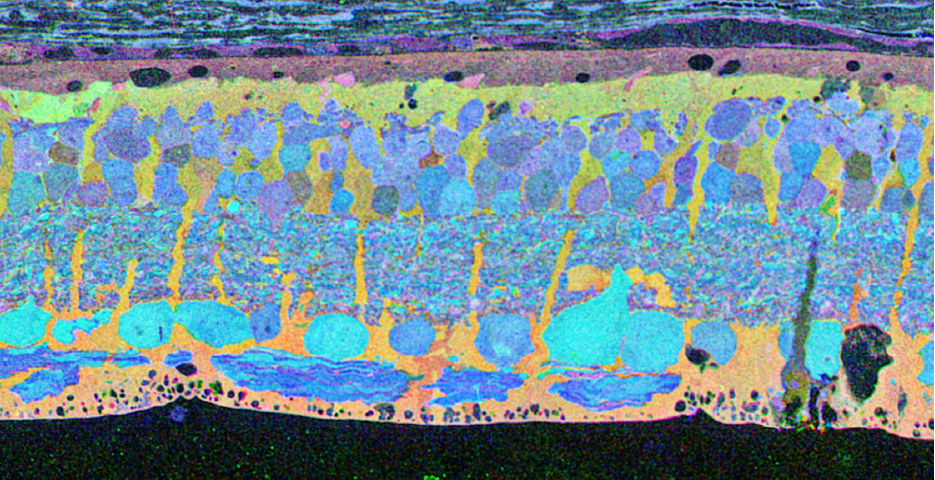

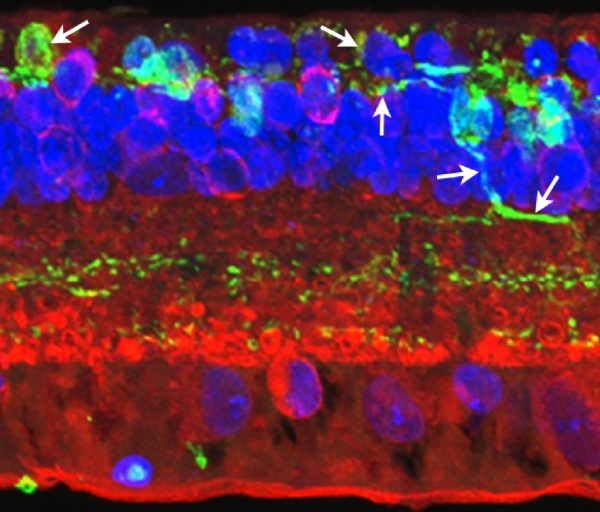

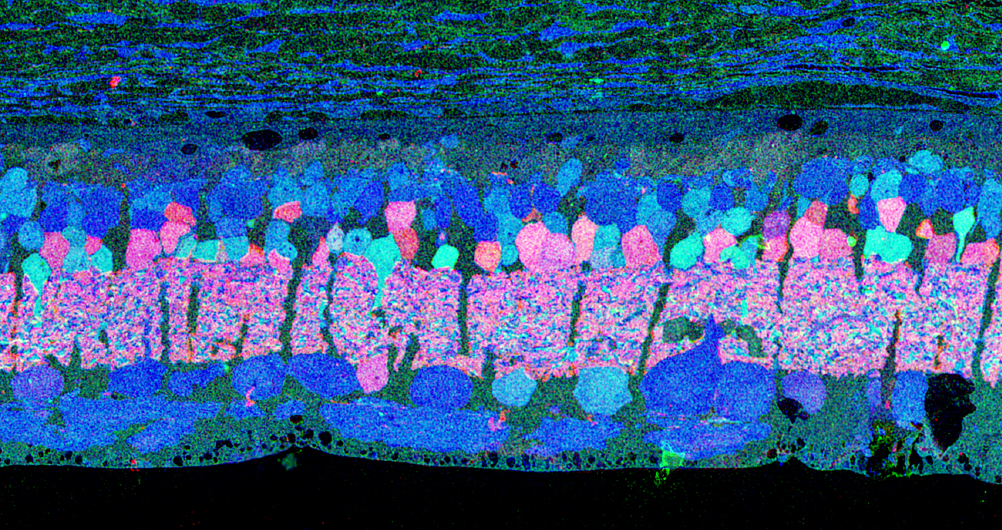

The year 2000 was also the year our research lab came into the retinal degenerative community with some reticence. Robert Marc had published 5 years previously, the first paper using Computational Molecular Phenotyping (CMP) (49) and we were busy using these technologies to explore mammalian and non-mammalian retinas. CMP is a fusion of 3 techniques including anti-hapten IgG libraries, tissue array fabrication and computational pattern recognition. CMP allows for simultaneous quantitative probing of multiple immunolabels (3-20 or more) with hapten-specific IgG probes with subcellular resolution in all cells. The technique profiles the metabolic state of every cell in a tissue. Figure 18 is a typical 3-space reconstruction of molecular data in human retinal tissue that uses red (r), green (g) and blue (b) color space to visually present differential labeling of small-molecule concentrations in tissues. In Figure 18, we can see taurine, glycine and glutathione represented, revealing the vascular choroid in blue at top, the RPE in pink, photoreceptor cell classes in orange, ON-cone bipolar cells with low concentrations of glycine in light green, due to coupling with AII and other glycinergic amacrine cells, and their fine processes extending down into the IPL in bright green.

We were interested and intensely focused on the normal circuitry of the retina and decidedly uninterested in pathology, but two events conspired to bring us into the field. The first event was a generous gift by Ann Milam of some human RP tissues to examine. At this point, we knew relatively little about retinal remodeling and were largely unaware of these few studies mentioned above. That said, upon processing the tissues that Dr. Milam had sent us, the following image is the first thing we saw.

This first image that came out of that initial analysis is shown in Figure 19. We were unprepared for what it revealed to us. In fact, it is fair to say that since we had no context to understand what we were seeing, we were completely flummoxed as the topology looked nothing like retina. In this image with the small molecular mapping as in Figure 18, you can see that the entire topology of the retina is altered. What should have been photoreceptors up at the top is now a Müller cell seal. Müller cells are in dark red. Glycinergic amacrine cells in bright green are jumbled and altered in their lamination and appearance. Isolated RPE cells are seen with punctate light green labeling throughout the retina and unknown glutathione rich cells are colored blue. Despite some curiosity, we did not know what to do with these tissues and set them aside returning to what we knew, the normal vertebrate retina.

The second event that brought us into the study of retinal degenerative diseases was a colleague, Jeanne Frederick who came by the lab with aged samples of GHL mice (adRP mimic) that she and Wolfgang Baehr had created (28), asking if I was interested in the retinas of “some old, blind mice”. The tissues Dr. Frederick was offering were osmicated and in blocks ready to be sectioned for transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and examined. CMP is compatible with TEM analysis, so we decided to see what aged mouse retina from a degenerate model looked like and we were stunned to see that these GHL mouse retinas looked precisely like the tissues from the human RP retinas that Ann Milam had sent and exhibited the same progressive degeneration as human RP retinas (Figure 20).

The problem with this was that there were more than a few papers that stated definitively that the neural retina was refractory to photoreceptor loss. To explore this conflict, we set out over the next couple of years to track as many retinal degenerative examples as we could find using both naturally occurring models and engineered models including the S334ter rat, P23H rat, RCS rat, rd1 mouse, the GHL mouse, TG9N mouse, nr, or, chx10, pcd, rd2, rho-/-, , rdcl, hrhoG, GC1&2 DKO, rhoDCTA mouse models as well as the P347L rabbit and the P23H pig. We also examined induced models like the light damage models and oxidative stress models. Colleagues from all over the planet were more than gracious in assisting us and some like Matt LaVail went above and beyond by contributing dozens of samples collected over the previous 30 years of work. The fundamental truth that came out of this work was that everywhere we looked in retinal degeneration, despite what was in much of the retinal transplant and vision rescue literature, we saw retinal remodeling from the molecular to the histologic scales.

The really stunning thing was how little work was in the literature at this time. For example, when we reviewed the literature in 2003, there were fewer than 30 papers in retinal degeneration that mentioned anything about inner retina neurons.

The remarkable thing about the community being misinformed about the state of the retina is that the histology in advanced forms of the disease, is dramatically altered from the normal appearance of the retina. One of the explanations might be that rodent models rarely get older than a year of age and for many investigators, once the photoreceptors were degenerated, they did not bother waiting longer for the more dramatic changes to ensue. That said, while aged rodent models of retinal disease are uncommon, there have been plenty of opportunities to study advanced human disease. Our explorations of advanced human RP have revealed dramatic alterations in the glial substrate as well as shown new structures termed microneuromas that form from neuritic sprouting from all neuronal cell classes in the retina (Figure 21).

It is also important to note that retinal remodeling and plasticity is not exclusive to RP and RP like disorders. In addition to human RP and models of RP, we’ve examined human AMD tissues and found extensive evidence of remodeling and retinal plasticity involving bipolar cells and Müller glia stress responses (23). Figure 22 is from a patient with an early geographic atrophy diagnosis. Notably, there are a couple other papers in the literature documenting remodeling in AMD (8, 50).

An induced model, light induced retinal degeneration (LIRD) in albino mice/rats represents a coherent stress insult to photoreceptors that results in massive loss of photoreceptors followed by subsequent retinal remodeling and reprogramming (31). Again, overall anatomical structure of the neural retina, particularly the inner nuclear layer, inner plexiform layer and ganglion cell layer seems normal or close to normal. However early in LIRD, key synaptic markers in inner retina demonstrate rapid inner retina responses to photoreceptor stress that lead to functional reprogramming of neuronal responses. This reprogramming is a result of AMPA GluR2 subunits largely associated with inner retinal processing, exhibiting rapid changes in protein level. GluR expression in LIRD changes over 60 days post light damage with low conductance AMPA receptor GluR2 subunits increasing 65% while high conductance KA receptor GluR5 subunits decrease 50%. AMPA receptor GluR1 subunits show no significant change in expression (51). Later in LIRD, there are massive changes and neuronal “escape” from the neural retina where bipolar and amacrine cells are observed leaving through breaks in Bruch’s membrane, into the choroidal space (Figure 23).

Another non RP model of retinal plasticity we have explored is the DBA/2J mouse model of glaucoma. Cuenca (52) demonstrated remodeling events in the ON-rod bipolar cells and horizontal cells in a increased pressure intraocular model in adult albino Swiss mice (52). Work in our lab in collaboration with Monica Vetter and Alejandra Bosco demonstrated remodeling events of GABAergic amacrine cell processes (Figure 24) which shows that negative retinal plasticity is not limited to photoreceptor deafferentations.

8. The TgP347L rabbit and P23H porcine models of retinitis pigmentosa

In addition to the mouse models, there are two viable large eye models of RP currently available. One, the P23H pig (53) shown in Figure 25 contains a Pro23His (P23H) rhodopsin (RHO) mutation that is the most common form of autosomal dominant RP (adRP) observed in humans. Porcine P23H models of RP show progressive loss of photoreceptors with loss of visual percepts as measured by ERG (53). Additionally, these porcine models demonstrate aberrant Müller cell signatures seen in human (Figure 22) and other models of retinal degeneration (Figure 30) with progressive loss of photoreceptors followed by loss of visual percepts as measured by ERG (53) just like the human rodent and rabbit (22, 23). Porcine tissues also exhibit neuritic sprouting in both the GABAergic and glycinergic amacrine cell populations prior to retinal photoreceptor degeneration, suggesting that there are stressors in the system that induce downstream responses in the inner neural retina.

The P347L TG rabbit was generated by Mineo Kondo and Hiroko Terasaki as a large eye model of autosomal dominant RP (54). The rabbit expresses a rhodopsin proline 347 to leucine transgene (Figure 26). Drs. Kondo and Terasaki approached us that same year to evaluate this model and compare it to models of RP as well as human RP. This work was published in 2011 documenting the progression of retinal degeneration and subsequent remodeling of the sensory and neural retina (22). We have analyzed degeneration, remodeling and reprogramming at the molecular level, physiological level, and the histological levels and have shown that disease progression in the TgP347L rabbit closely tracks human cone-sparing RP, including the cone-associated preservation of bipolar cell signaling and triggering of glutamate channel reprogramming.

The TgP347L rabbit as well as the P23H pig model are attractive as models of retinal disease for a number of reasons. This model is a large eye model and there is a substantial existing knowledge base in ophthalmology including retinal anatomy and circuitry. Some advantages of the TgP347L rabbit is the relatively fast disease progression combined with a manageable and affordable approach making the TgP347L rabbit an excellent model for gene therapy, cell biological intervention, progenitor cell transplantation, surgical interventions and bionic prosthetic studies.

Because of the similarity of the TgP347L rabbit to human adRP, most of the remodeling specific discussion that follows will derive from data from that model system.

Retinal degeneration in the mammalian retina occurs in phases. Phase 1 is typified by photoreceptor stress which is the beginning of early remodeling & clinically occult reprogramming events at the cellular and molecular levels. Phase 2 of retinal remodeling involves the microglia, Müller glia and RPE cells as the Müller glia begin to exhibit signs of cell stress and reactivity to the degenerating retina. Müller cells also begin to hypertrophy and grow up between photoreceptor cells to initiate the Müller cell seal. Cell death in the ONL begins to occur in Phase 2 as well. Phase 3 is where we begin to see neuritic sprouting from all neural cell classes resulting in new neuronal circuits. Neuronal cell death also begins to occur in the bipolar, horizontal and amacrine cell populations. The end stage of retinal remodeling is a neural retina bereft of cells and unable to signal coherent visual pathways to higher centers for processing.

Progression of retinal degeneration and remodeling in the Tg P347L rabbit closely tracks the sequelae of events seen in human RP, though it appears to happen at an accelerated rate progressing to total photoreceptor loss at 1yr of age. At 12-16 weeks in the TgP347L rabbit, Phase 1 of retinal remodeling has begun early in the retinal degenerative process before photoreceptors have degenerated. The photoreceptor structure appears largely intact with the exception of some disorganization in the outer segments of photoreceptors. Some portions of outer segments break off and appear to remain in the subretinal space, rather than being phagocytosed by the RPE (Figure 27). The most compelling feature of this region is the large numbers of small vesicular rod photoreceptor outer segments that break off and appear as a rhodopsin “froth” in the subretinal RPE/photoreceptor interface space. We speculate that this “froth” increases oxidative cell stress in RPE and photoreceptor cells.

By 40 weeks in the Tg P347L rabbit, some opsin expression can still be found in cones, however, it is delocalized much like what was described in Li et. al in 1995 (1). While photoreceptors can still be found in abundance, the rhodopsin delocalization into the membrane surrounding the cell body suggests substantial photoreceptor cell stress (23).

Figure 28 shows glutamine immunoreactivity in Phase 1-2 in the Tg P347L rabbit retina at 4 months where the glutamine signal begins to demonstrate alterations between Müller cells. Glutamine is present in most retinal neurons, but most notably in Müller cells. It is also found at high concentrations in the RPE cells, but at 4 months, glutamine levels in isolated Müller cells are revealing multiple metabolic states, a result never observed in normal retina (22).

Further into Phase 2 at 10 months in the Tg P347L rabbit retina, glutamine synthetase (GS) levels also show quantifiably different levels of expression (Figure 29). GS mediates the recycling of glutamate, GABA and ammonia to form glutamine, and becomes dramatically unregulated in some Müller glia, explaining the mosaicked levels of glutamine observed in Figure 28, but also revealing specifically that nitrate reduction and amino acid degradation pathways are being altered in the degenerate retina (22).

CMP visualization in the 10 month old TG P347L rabbit retina in Phase 2-3 with tQE :: rgb (t-taurine, red; Q-glutamine, green; E-glutamate, blue) visualization (Figure 30) allows retinal pigmented epithelium and Müller cells to be observed independent from all other cell classes. In this visualization, L-glutamate labeling in combination with taurine demonstrates 3 surviving cones protruding above the Müller cell seal (pink cells). Additionally, the mosaicism in the Müller cell signatures is evident demonstrating the pathological heterogeneity of small molecular signals. In this region of retina, the Müller cell seal is essentially complete, isolating the neural retina from the RPE and choroid and the retina is bereft of any photoreceptors save the 3 isolated cone photoreceptors in this region (22).

Figure 31. Maximal projection image of PKC (red), Rho 1D4 (green), and DAPI (blue) in the Tg P347L rabbit retina. Figure demonstrates reduced rhodopsin immunoreactivity (green spots in ONL) and some rod bipolar cell (red) with aberrant dendrites and axons (small arrows) compared with normal rod bipolar axon terminals in the lower IPL (white bracket , at).

Phase 3 is typified by extensive, de novo neurite formation, new synapse formation and neuronal death. In the Tg P347L rabbit, the retina is fully involved in Phase 3 remodeling by 10 months. Maximal projection confocal images of protein kinase C immunoreactivity (PKC), rhodopsin 1D4 immunoreactivity (Rho 1D4) and a nuclear stain (DAPI) :: rgb demonstrate not only the reduced rhodopsin immunoreactivity associated with degenerate rod photoreceptors, but also bipolar cell axons that have become multipolar cells, projecting along the top border of the IPL (Figure 31). These processes extend outside of the normal lamination of the bipolar cell population, coursing across the IPL, forming swellings also suggestive of synaptic connectivities and implying new retinal connectivities (22). These bipolar cells also are downregulating iGluR and mGluR6 expression, results observed previously in rodent and human retinal degenerative diseases (31).

In another region of Tg P347L rabbit retina at 10 months, Phase 3 remodeling can also be documented through persistent neurite formation of horizontal cells. In Figure 32, a maximal projection confocal image shows immunohistochemistry of PKC, calbindin (a calcium binding protein) and DAPI :: rgb, demonstrating calbindin labeling in horizontal cells. Horizontal cell processes are seen projecting down into the IPL in an aberrant fashion (22). Calbindin has been used extensively before to examine alterations in the horizontal cell populations (4) and these results correlate nicely with those observed in the human retina.

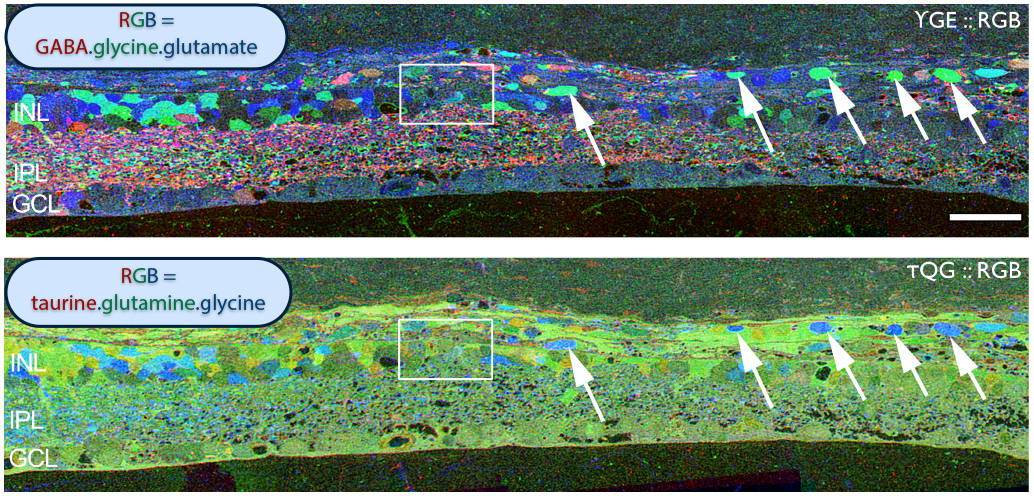

Examining neuritic sprouting from amacrine cells in the Tg P347L rabbit in Phase 3 at 10 months shows new GABAergic and glycinergic neurite formation. Figure 33 is a yGE :: rgb visualizing photoreceptor, bipolar cell, GABA+(g) and glycine+(G) amacrine cells and glutamate+ (E) ganglion cell superclasses. Overall the lamination of the IPL appears normal, but this belies excitatory and inhibitory cell populations in these retinas that are creating new neurites, seen here as fine filamentous magenta signals running underneath the Müller cell seal seen in Figure 30, and above most remaining bipolar cell populations (22).

Figure 34. GABA channel from Figure 33 showing increased expression of GABA in the Müller cells and anomalous neurites from GABAergic amacrine cells running beneath the Müller cell seal.

Figure 34 shows GABA labeling in phase 3 of remodeling in the Tg P347L rabbit retina at 10 months, revealing GABAergic amacrine cell sprouting. Again, the overall lamination of the IPL revealed by GABA immunoreactivity appears normal. Though early GABAergic sprouting events. Persistent neurite formation, new synapse formation and neuronal death (22). This is still early in Phase 3, prior to large scale topographic reorganization which occurs as Müller cells continue hypertrophic responses and additional numbers of cells from each cell class undergo cell death.

Sprouting from amacrine, bipolar, horizontal and ganglion cell populations can continue to elaborate their structures, forming large tangles of GABAergic, glycinergic and glutamatergic processes into microneuromas or tufts of neuropil formed de novo post retinal maturation and development. These microneuromas break traditional rules of plexiform lamination and can be seen in Figure 35 in the hrhoG mouse erupting out of the IPL and coursing up to the top of the retina underneath the RPE.

By late stage in Phase 3, persistent neurite formation, new synapse formation and neuronal death continue with all cell classes participating. As cell classes continue to sprout processes from bipolar, amacrine, horizontal and ganglion cells, many processes begin to co-fasiculate and run together in structures called microneuromas complete with synaptic connectivity. Figure 36 is a collection of neuritic processes moving from one location to another within an area of Müller cell seal. Microneuromas are not silent structures as they contain both ribbon and conventional synapses with a number of synaptic arrangements including, but not exclusively amacrine > amacrine, bipolar > amacrine, and amacrine > bipolar and bipolar > bipolar (9).

9. The earliest changes in the retina occur before obvious histological changes occur.

In models of RP where rods and cones die simultaneously, bipolar cells lose dendrites and all iGluR/mGluR responsivity. From Phase 0-1, rod bipolar cells down-regulate GluR expression in the dendrites. In Phase 1-2, rod and cone photoreceptor stress and subsequent cell death happen, while dendritic modules are lost. In Phase 3, wider retinal remodeling ensues, resulting in sprouting and formation of new axonal modules. In models of RP where cones outlive rods, some bipolar cell dendrites switch targets. In normal rod bipolar cell architecture, dendrites from rod bipolar cells bypass cone pedicles. In Phase 0-1, as in rod/cone dystrophies, rod bipolar cells down regulate GluR expression in the dendrites. In Phase 1-2 with rod stress and death, dendritic modules are lost. In late Phase2/Phase 3, some rod bipolar cells form sprouts that contact cone pedicles, making peripheral contacts on cone pedicles. Figures 37 and 38 summarizes the degenerative phases that a retina with RP type degeneration go through as described above. In human RP it is clear that the peripheral retina goes into phases 1-3 long before the central retina and fovea does. The RP patient eyes that have been looked at with good anatomical techniques have phase 3 retina in the periphery and phase 1 in the fovea (4, 44, 46, 47, 55).

10. Conclusion

Fundamentally, in every instance of retinal disease and model of retinal degeneration examined to date, the survival of cones appears to at least delay the gross onset of Phase 3 remodeling. This can be seen in local patches of retina where cones persist with preserved bipolar cell dendritic structures. Even when cones are severely compromised and lack outer segments, visual pigment expression and altered morphology, as long as cones are present, the retina appears to maintain its state in Phase 2. This may suggest the involvement of integrins or demonstrate that mere connectivity through the established circuit is enough to maintain Ca++ signaling and gene expression profiles. At the very least, it provides evidence that prolonging cone survival is a substantial advantage to maintaining vision or making subsequent vision rescues such as survival factors, stem or progenitor cell transplantation, fetal retinal sheet transplantation and gene therapies more successful.

As we move forward into genetic models with various treatments designed to delay or recover vision loss, we need to consider the potential shown by plasticity in the retina. Retinal remodeling in phase 1 and 2 might for instance, be reversible and may in fact respond to the right therapeutic interventions. However, by the time the retina enters Phase 3, with its alterations to wiring and neuritogenesis, cell migration and cell death, it is likely too late. The problem with gene therapies for rods and cones is that they depend upon photoreceptor survival. If we can prolong cone survival, this might point the way to a “cure”. However, as we noted above, photoreceptor involvement in retinal degenerative disease begins long before the photoreceptors die. This begins to define “windows of opportunity” where gene therapies might succeed and also suggests that combination gene therapy with survival factor administration might be a reasonable approach to prolong photoreceptor survival through delivery of neurotrophins.

References:

1. Li ZY, Kljavin IJ, Milam AH. Rod photoreceptor neurite sprouting in retinitis pigmentosa. J Neurosci. 1995;15:5429–5438. [PubMed]

2. de Raad, S., et al., Light damage in the rat retina: glial fibrillary acidic protein accumulates in Muller cells in correlation with photoreceptor damage. Ophthalmic Res, 1996. 28(2): p. 99-107. [PubMed]

3. Fletcher, E.L. and M. Kalloniatis, Neurochemical architecture of the normal and degenerating rat retina. J Comp Neurol, 1996. 376(3): p. 343-60. [PubMed]

4. Fariss, R.N., Z.Y. Li, and A.H. Milam, Abnormalities in rod photoreceptors, amacrine cells, and horizontal cells in human retinas with retinitis pigmentosa. Am J Ophthalmol, 2000. 129(2): p. 215-23. [PubMed]

5. Machida S., Kondo M., Jamison J.A., Khan N.W., Kononen L.T., Sugawara T., Bush R.A., Sieving P.A., P23H rhodopsin transgenic rat: correlation of retinal function with histopathology. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, 2000. 41(10): p. 3200-9. [PubMed]

6. Strettoi E, Pignatelli V. Modifications of retinal neurons in a mouse model of retinitis pigmentosa. Proc Natl Acad Sci 2000. 97:11020– 11025. [PubMed]

7. Strettoi E, Porciatti V, Falsini B, Pignatelli V, Rossi C. Morphological and functional abnormalities in the inner retina of the rd/rd mouse. J Neurosci, 2002. 22(13): p. 5492-504. [PubMed]

8. Sullivan, R., P. Penfold, and D.V. Pow, Neuronal migration and glial remodeling in degenerating retinas of aged rats and in nonneovascular AMD. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, 2003. 44(2): p. 856-65. [PubMed]

9. Jones, B.W., et al., Retinal remodeling triggered by photoreceptor degenerations. Journal of Comparative Neurology, 2003. 464: p. 1-16. [PubMed]

10. Marc, R.E. and B.W. Jones, Retinal remodeling in inherited photoreceptor degenerations. Mol Neurobiol, 2003. 28(2): p. 139-47. [PubMed]

11. Marc RE, Jones BW, Watt CB, Strettoi E. Neural remodeling in retinal degeneration. Prog Retin Eye Res, 2003. 22(5): p. 607-55. [PubMed]

12. Cuenca, N., et al., Regressive and reactive changes in the connectivity patterns of rod and cone pathways of P23H transgenic rat retina. Neuroscience, 2004. 127(2): p. 301-17. [PubMed]

13. Cuenca, N., et al., Early changes in synaptic connectivity following progressive photoreceptor degeneration in RCS rats. Eur J Neurosci, 2005. 22(5): p. 1057-72. [PubMed]

14. Jones, B.W. and R.E. Marc, Retinal remodeling during retinal degeneration. Exp Eye Res, 2005. 81(2): p. 123-37. [PubMed]

15. Jones, B.W., C.B. Watt, and R.E. Marc, Retinal remodelling. Clin Exp Optom, 2005. 88(5): p. 282-91. [PubMed]

16. Jones, B.W., et al., Neural plasticity revealed by light-induced photoreceptor lesions. Adv Exp Med Biol, 2006. 572: p. 405-10. [PubMed]

17. Pu, M., L. Xu, and H. Zhang, Visual response properties of retinal ganglion cells in the royal college of surgeons dystrophic rat. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, 2006. 47(8): p. 3579-85. [PubMed]

18. Aleman, T.S., et al., Inner retinal abnormalities in X-linked retinitis pigmentosa with RPGR mutations. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, 2007. 48(10): p. 4759-65. [PubMed]

19. Specht D, Tom Dieck S, Ammermüller J, Regus-Leidig H, Gundelfinger ED, Brandstätter JH. Structural and functional remodeling in the retina of a mouse with a photoreceptor synaptopathy: plasticity in the rod and degeneration in the cone system. Eur J Neurosci, 2007. 26(9): p. 2506-15. [PubMed]

20. Marc RE, Jones BW, Watt CB, Vazquez-Chona F, Vaughan DK, Organisciak DT. Extreme retinal remodeling triggered by light damage: implications for age related macular degeneration. Mol Vis, 2008. 14: p. 782-806. [PubMed]

21. Stasheff, S.F., Emergence of sustained spontaneous hyperactivity and temporary preservation of OFF responses in ganglion cells of the retinal degeneration (rd1) mouse. J Neurophysiol, 2008. 99(3): p. 1408-21. [PubMed]

22. Jones, B.W., Kondo, M., Terasaki, H., Watt, C.B., Rapp, K., Anderson, J., Lin, Y., Shaw, M.V., Yang, J-H., Marc, R.E., Retinal Remodeling in the Tg P347L Rabbit, a Large-Eye Model of Retinal Degeneration. J Comp Neurol, 2011. Oct 1;519(14): 2713-33. [PubMed]

23. Jones, B.W., Kondo, M., Terasaki, H., Lin, Y., M. McCall and Marc, R.E., Retinal Remodeling. 2012 Jpn J Ophthalmic 56 (4); 289-306. [PubMed]

24. Baehr, W. and J.M. Frederick, Naturally occurring animal models with outer retina phenotypes. Vision Res, 2009. 49(22): p. 2636-52. [PubMed]

25. Chang CJ, Lai WW, Edward DP, Tso MO. Apoptotic photoreceptor cell death after traumatic retinal detachment in humans. Arch Ophthalmol, 1995. 113(7): p. 880-6. [PubMed]

26. Lewis GP, Linberg KA, Fisher SK. Neurite outgrowth from bipolar and horizontal cells following experimental retinal detachment. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci.1998;39:424–434. [PubMed]

27. Humphries MM, Rancourt D, Farrar GJ, Kenna P, Hazel M, Bush RA, Sieving PA, Sheils DM, McNally N, Creighton P, Erven A, Boros A, Gulya K, Capecchi MR, Humphries P. Retinopathy induced in mice by targeted disruption of the rhodopsin gene. Nat Genet, 1997. 15(2): p. 216-9. [PubMed]

28. Frederick J.M., Krasnoperova N.V., Hoffmann K., Church-Kopish J., Rüther K., Howes K., Lem J., Baehr W. Mutant rhodopsin transgene expression on a null background. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001 mar;42(3): 826-33. [PubMed]

29. Jones B.W., Pfeiffer R.L., Ferrell W.D., Watt C.B., Marmor M., Marc R.E.. Retinal remodeling in human retinitis pigmentosa. Experimental Eye Research 2016 150, 149-165 [PubMed]

30. Jones B.W., Pfeiffer R.L., Ferrell W.D., Watt C.B., Tucker J., Marc R.E.. Retinal remodeling and metabolic alterations in human AMD. Frontiers in cellular neuroscience 10.

31. Marc RE, Jones BW, Anderson JR, Kinard K, Marshak DW, Wilson JH, Wensel T, Lucas RJ. Neural reprogramming in retinal degeneration. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science, 2007. 48(7): p. 3364-3371. [PubMed]

32. Gesine B. Jaissle, Christian Albrecht May, Serge A. van de Pavert, Andreas Wenzel, Ellen Claes-May, Andreas Gießl, Peter Szurman, Uwe Wolfrum, Jan Wijnholds, M. D. Fisher, P. Humphries, M. W. Seeliger. Bone spicule pigment formation in retinitis pigmentosa: insights from a mouse model. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2010 Aug;248(8):1063-70. [PubMed]

33. Marc RE. Functional Neuroanatomy of the Retina in Albert and Jakobiec’s Principles and Practice of Ophthalmology, 3rd edition (Eds Albert and Miller) 2008 Elsevier, pp. 1565-1592. [pdf]

34. Cajal S. R. The Structure of the Retina. Book Translated by Sylvia A. Thorpe and Mitchell Glickstein, 1972. Charles C. Thomas Publisher, Springfield ILL.

35. Hinds J.W., Hinds P.L. Early development of amacrine cells in the mouse retina: an electron microscopic, serial section analysis. J Comp Neurol. 1978 May 15;179(2):277-300. [PubMed]

36. Lenkowski JR, Raymond PA. Müller glia: Stem cells for generation and regeneration of retinal neurons in teleost fish. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2014 May;40:94-123 [PubMed]

37. Raymond P. A. Retinal regeneration in teleost fish. Ciba Found Symp. 1991;160:171-86; discussion 186-91.

38. Fadool J.M. Development of a rod photoreceptor mosaic revealed in transgenic zebrafish. Dev Biol 2003 June 15;258(2):277-90 [PubMed]

39. Jacobsen M. Developmental Neurobiology Holt, Rinehart and Winston inc NY, Chicago, SF, Atlanta, Dallas, Montreal, Toronto, London, Sydney 1970

40. Menger GJ, Koke JR, Cahill GM. Diurnal and circadian retinomotor movements in zebrafish. Vis Neurosci. 2005 Mar-Apr;22(2):203-9. [PubMed]

41. Wagner H-J. Darkness-induced Reduction of the Number of Synaptic Ribbons in Fish Retina. Nature New Biology. 1973;246:53-55. [PubMed]

42. Dowling JE. Organization of vertebrate retinas. Investigative Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences. 1970, Sep;9(9): 655-80. [PubMed]

43. Peichl L., Bolz J. Kainic acid induces sprouting of retinal neurons. Science 1984 Feb 3;223(4635):503-4. [PubMed]

44. Kolb H., Gouras P. Electron microscopic observations of human retinitis pigmentosa, dominantly inherited. Invest Ophthalmol. 1974 Jul;13(7):487-98. [PubMed]

45. Mizuno K,, Nishida S. Electron microscopic studies of human retinitis pigmentosa. 1967 Am. J. Ophthalmol. 63, 791. [PubMed]

46. Szamier RB and Berson EL. Retinal ultrastructure in advanced retinitis pigmentosa. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1977 Oct;16(10):947-62. [PubMed]

47. Szamier RB, Berson EL, Klein R, Meyers S. Sex-linked retinitis pigmentosa: ultrastructure of photoreceptors and pigment epithelium. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1979 Feb;18(2):145-60 [PubMed]

48. Chu Y, Humphrey MF, Constable IJ. Horizontal cells of the normal and dystrophic rat retina: a wholemount study using immunolabeling for the 28 kDa calcium binding protein. Exp Eye Res. 1993;57:141–148. [PubMed]

49. Marc, R.E., R. Murry, S.F. Basinger 1995 Pattern recognition of amino acid signatures in retinal neurons. J Neurosci 15:5106-5129. [PubMed]

50. Sullivan, R., E. Woldemussie, and D.V. Pow. Dendritic and synaptic plasticity of neurons in the human age-related macular degeneration retina. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, 2007. 48(6): p. 2782-91. [PubMed]

51. Lin Y., Jones B.W., Liu A., Vazquéz-Chona F.R., Lauritzen J.S., Ferrell W.D., Marc R.E. Rapid glutamate receptor 2 trafficking during retinal degeneration. Molecular Neurodegeneration 2012, 7:7 doi:10.1186/1750-1326-7-7 [PubMed]

52. Cuenca N, Pinilla I, Fernández-Sánchez L, Salinas-Navarro M, Alarcón-Martínez L, Avilés-Trigueros M, de la Villa P, Miralles de Imperial J, Villegas-Pérez MP, Vidal-Sanz M., Changes in the inner and outer retinal layers after acute increase of the intraocular pressure in adult albino Swiss mice. Exp Eye Res, 2010. 91(2): p. 273-85. [PubMed]

53. Ross JW, Fernandez de Castro JP, Zhao J, Samuel M, Walters E, Rios C, Bray-Ward P, Jones BW, Marc RE, Wang W, Zhou L, Noel JM, McCall MA, DeMarco PJ, Prather RS, Kaplan HJ. Generation of an inbred miniature pig model of retinitis pigmentosa. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012 Jan 31;53(1):501-7. [PubMed]

54. Kondo M, Sakai T, Komeima K, Kurimoto Y, Ueno S, Nishizawa Y, Usukura J, Fujikado T, Tano Y, Terasaki H. Generation of a transgenic rabbit model of retinal degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, 2009. 50(3): p. 1371-7. [PubMed]

55. Bonilha VL, Rayborn ME, Li Y, Grossman GH, Berson EL, Hollyfield JG. Histopathology and functional correlations in a patient with a mutation in RPE65, the gene for retinol isomerase. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011. 52(11): p. 8381-92. [PubMed]

The authors:

Bryan William Jones, Ph.D., is Associate Research Professor at the John A. Moran Eye Center at the University of Utah. His work involves disorders of retinal degeneration and how those diseases affect the intrinsic retinal circuitry including the implications for rescue of vision via gene therapy, and retinal bionic or biological implants. Other research efforts involve exploring metabolomics for application in understanding physiology and medicine and for drug development.

Robert E. Marc, Ph.D., is Distinguished Emeritus Professor of Ophthalmology at the John A. Moran Eye Center at the University of Utah. Robert is currently the co-owner of Stray Arrow Ranch, and CEO of Signature Immunologics and is credited with the creation of Computational Molecular Phenotyping, developing channel mapping and visualization technologies as well as building the first comprehensive connectome with the resolution and features required to identify neurons and map connectivities.

Rebecca L. Pfeiffer, PhD, is currently a Postdoc in the Jones Lab at the John A. Moran Eye Center at the University of Utah. Her research focus is on understanding the progression of retinal disease and the involvement of both neurons and glia. This is being evaluated using a combined metabolomics and connectomics approach to assess the progression of retinal remodeling and neurodegeneration.

Our thanks to Mineo Kondo and Hiroko Terasaki for making this work possible:

Mineo Kondo, M.D., Ph.D., Professor of Ophthalmology, Mei University Graduate School of Medicine, Tsu, Japan and is responsible along with Hiroko Terasaki for the generation of the P347L rabbit. Mineo’s work focuses on using the electroretinogram for the diagnosis of various retinal diseases as well as exploring animal models of human retinal and optic nerve diseases.

Hiroko Terasaki, M.D., Ph.D., is Professor and Chairman of Ophthalmology at Nagoya University Hospital. Hiroko is responsible, along with Mineo Kondo for producing the P347L rabbit model of retinal degenerative disease. Professor Terasaki received her medical and ophthalmological training at the Medical School of Nagoya University under the tutorship of emeritus Professors Hiroshi Ichikawa, Shinobu Awaya, and Yozo Miyake. She was also trained at the Schepens Eye Research Institute in Boston, MA under the guidance of Professor Tatsuo Hirose.